Zeleny, Kyler. Bury Me in the Back Forty. The Velvet Cell. Berlin 2024.

Zeleny, Kyler. Crown Ditch and the Prairie Castle. The Velvet Cell. Berlin 2020.

Zeleny, Kyler. Out West. The Velvet Cell. Berlin 2014.

Part 1: Getting Out West

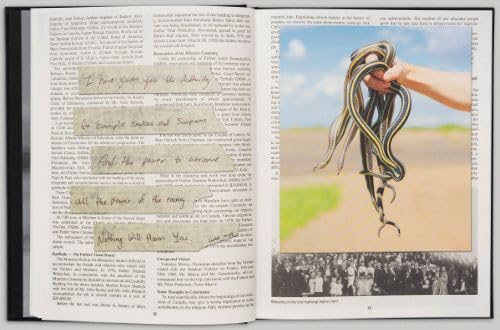

Kyler Zeleny roams the prairies, seeking and capturing stories through his lens. He pays homage to those left behind: the old, the poor, the marginalized, and the stubborn, who allow themselves to be seen. The younger generations, however, leave, trading dusty Wranglers for modern conveniences—or as Kyler puts it, “for kale and kombucha.”

Kyler and I met as graduate students over a decade ago, but only now do I fully grasp the significance of his work. Kyler’s work stands like a lone grain elevator against material lack of empirical phenomenological rural visual ethnography. The North American Western Prairies, particularly those north of the U.S.-Canada border, have never received enough attention.

Kyler’s work is unique in its combination of photography and academic text. He has worked tirelessly to reach a broader audience, contributing opinion pieces to national outlets like The Globe and Mail, and MacLeans and international ones like The Guardian. These efforts have brought greater attention to those who dwell in the middle. However, as any marginalized population will tell you, most folks just want to be left alone. Moreover, the image-saturated public has a finite capacity for consuming more images. Kyler’s Prairie trilogy offers an opportunity to slow down between the covers, of yes, a printed book without hyperlinks, pop-up ads, and endless distraction.

Reappraising Kyler’s work brought new clarity when I encountered the text alone. As I read, my mind formed connections and mental images informed by Kyler’s photographs, making the stories come alive. It is this movement—life itself—that embodies the spirit of his images and text. They vividly depict the death of a certain kind of prairie farmer, rancher, and the poor in their own places.

Kyler has tried to show me that as the people—the characters—die, the places will, and are, dying too. The mud, straw, and weathered wood structures that dot the prairies—places most will never see—are disappearing. When people in Britain saw Humphrey Lloyd Heim’s survey images of Prairie Looking West, the common refrain was, “There is nothing there.”

Part 2: Whispered Histories in Bury Me…

“…absent from but entirely within the landscape”

-Deleuze and Guattari (What is Philosophy, p. 169)

Bury Me is darker than previous efforts—a lament, a kind of empirical solastalgia. It serves as a portal into stories and memories accessed through alcohol, a substance normalized and protected as a cultural practice.

Readers are warned that some of these stories are not meant for us, though we may be rewarded if we patiently seek meaning. For me, with a family settler lineage geographically close to Kyler’s, the Canadian-Ukrainian prairie dialect—known colloquially as half na piw (half and half)—is familiar.

Bury Me extends the automotive-driven Crow Ditch and provides a socially accepted refuge from the geographic alienation of rural existence. This third installment, the capstone of what might be called a Prairie Gothic Trilogy, feels like both the apex and the conclusion of a building momentum. (see George Webber, Prairie Gothic, 2013). The momentum has been built by Zeleny’s life within these fading stories, and as a cultural geographer, he poses the rhetorical question: “If a rural dweller dies alone, and no one is there to hear it…?”

In juxtaposing pastoral scenes with recreational vehicles on fire, or immigrant settler dwellings of mud and straw cut with the headless torsos of contemporary memory keepers, we see a resistance to the slow, monolithic march of time. There is also a need to make intelligible the lived experience of a cultural form of existence unique to a place—and unique because of its limited participation. Neighbours live miles apart, and young people eventually leave for the city. The conditions have been primed for forgetting.

“What does it mean to lean your bones against this landscape?”

I wonder, what does it mean to lean against the dust of the bones, or as Zeleny says, “more dust than dance. More virtual than actual.”

Part 3: Erosion and Nostalgia: Toward a Philosophy of Topo-roder-stalgia

Nostalgia, derived from the Latin solacium (comfort) and the Greek algia (pain, suffering, and grief), describes emotional or existential distress caused by environmental change, distinct from the eco-anxiety associated with pre-traumatic stress.

Deculturation occurs when an individual or minority group loses cultural identity, leading to alienation, acculturative stress, and potentially ethnocide. Cultural erosion refers to the loss of unique cultural practices, beliefs, and traditions. In an Indigenous context, this can also mean genocide and cultural genocide.

Zeleny’s work suggests a new theoretical framework to describe the impact of losing a place shaped by temporary (100 years) community and social formations that eventually vanish.

In his doctoral dissertation, Zeleny explores the concept of the post-photographic (Mitchell 1992), arguing that everything has been photographed. The next steps, therefore, involve pastiche, collage, and bricolage. We must peer back through layers of built-up materials and images, scratch the surface, mark them up, peel them back, and re-layer.

What word, then, captures the slow-drip evacuation of the Prairie Settler era? Erosionalgia? Rodere-stalgia? Topo-roder-stalgia?

If we were theorizing in German or even French, specificity might lead us to topo-roder-stalgia. We need a term to differentiate cultural and emotional loss driven by changing social patterns in relation to economic flows, rather than environmental forces.

Zeleny’s trilogy engages with place explorations akin to those of rural Italy and rural Japan, where property is sold at a fraction of the cost of real estate in Milan or Tokyo. In addition to post-photographic peeling, peering, and layering, Zeleny’s work also engages with Indigenous histories on Turtle Island.

Cree scholar Dwayne Donald uses the art historian term pentimento (Donald 2004, Canadian Association for Curriculum Studies) to describe how relics of a built environment or the song lines of Keith Basso’s Apache ethnography (Basso 1996, Wisdom Sits in Places) offer glimpses into stories that, like Zeleny suggests, might not be for us. Most of us lack the patience to peer back or peel back these layers of stories.

Zeleny is a modern historian of a limited history, one that begins in the late 1800s with Ukrainian immigrants who were recruited to settle in Canada. This history layers over an existing migratory culture, erasing Indigenous ways of being. While Indigenous people were primarily mobile and migratory, land ownership was not an operating concept, though treaties between bands existed.

Ukrainians in the late 1800s, and again throughout the 1920s and 1940s, were seen as visually similar to white Anglo-Saxon, British, and French settlers. Only their language and religion needed to be assimilated.

Zeleny’s work resists these final stages of assimilation by including small fragments of Ukrainian translations in the Cyrillic alphabet. His use of regional history books, the Mundare volume, promoted by the Canadian government in the late 1970’s and early 1980’s adds another layer. These books, bound in hardcovers, suggest a “complete” history of a place—a way to confront Humphrey Lloyd Heim’s notion that “there is nothing there.” If there is a bound hardcover book, there must be something there.

These regional history books define an area, acknowledge the land—circa 1980—and provide a mile-by-mile, square-by-square family history accounting of settlement patterns. The ethos was completeness. Government grants enabled groups of amateur historians to solicit written entries from families and knowledge keepers to assemble these records, detailing family histories, homestead clearings, modern dwelling reconstructions, and the arrival of electricity. These books, like the ones on my shelves, remain. Kyler reminded me that, similar to deeds and titles, these books are highly coveted. When someone dies, siblings often argue over who gets to keep them.

Part 4: Recounting and Reappraisal

This conversation is academic. The settler-descendant people of the western Canadian prairies have at most a 150-year history in Canada. Indigenous people, such as the Dene, Cree, and Blackfoot, have a much longer history in this place. To his credit, Zeleny is aware of this on-top-of-ness – and he works to focus on the uniqueness of the cultural formation, buildings, places, people, and signs, of the more recent past.

Zeleny’s work follows a chronological history as a memory keeper and signifier of people, place, and time. A time that changes as the wind erodes structures and ways of life.

The Hardcovers of what I want to call the Prairie Gothic trilogy stand next to my copies of those regional history books from the 1980s that my grandmother helped create. The materiality of the photographs and text bound in hardcover pages stand like gravestones. These books announce, and radiate from their spines and covers – the stories within.

Occasionally, a story is revealed to those who are patient and willing to listen and understand. Zeleny is a prospector of stories and he takes time to travel and listen, and patiently douse for more.

I am troubled by the dominance of text and images in a world that undervalues oral traditions, which sustained people for thousands of years. Our attachment to these mediums is evident in printed books, magazines, art shows, and online images, leaving us overwhelmed and unable to make sense of it all—leading to a post-photographic era of saturation without meaning.

These books stand as a testament, a sign within the spatial and temporal intersection of settler communities in sparsely populated prairie places, where once there were more people, and now there are fewer.

Post-photographic is a useful term to view Zeleny’s work as an opportunity to adjust through collage, ink, modification, and creation.

Topo-roder-stalgia is useful in understanding Zeleny’s sustained contribution over three texts as a way to process the fact that the landscape of people and place is being gnawed away on many fronts.

Eventually, all that will remain are a few books, some weathered wood, and a new generation that gazes at the prairie landscape and thinks, not that there is nothing there, but that there was once something—some lives, and ways of being—but we can’t quite remember or imagine what.

-Andriko Lozowy (Concordia Univ.)