Justine Lloyd, Sydney

Sounding Two, 6 December 1925

These interplays between placemaking, radio audiences and Sydney’s waterways were not the first outside broadcasts to focus on the harbor as a stage for radiophonic experiences, however. These cosy and celebratory modes of inhabiting the harbor aboard the cruising broadcasts of the Children’s Session in the 1930s can be contrasted with the earliest harbor-based broadcasts. During the 1920s, radio events at the harbour employed newly portable analogue microphones, together with telephonic transmission and radio technologies to reach from the floor of the harbour to the private home. These radiophonic experiments were invoked to promote engineering feats involving undersea tunnelling at the time. The mediation of these newly invaded spaces invited the radio audience to participate by extending the human senses into previously unheard realms. These types of harbor experiences were only accessible through modern engineering practices, and implicated in the problematic of ‘audio travelling’: what would these places sound like? How would the audience know that they were ‘there’ when they got there? And what kinds of knowledges of exotic environments would they evoke?

During the early 1920s, acoustic investigations of remote or previously inaccessible spaces were intensely anticipated. Radio audiences were interested in descriptions of views which were beyond human experience just a few years earlier. Broadcasters’ ideas for such events included aerial feats such flying over the city and harbor and describing the experience live over the radio from a plane, and underground possibilities included taking radio broadcasting equipment into chthonic zones such as the spectacular limestone formations of Jenolan Caves in southern NSW, or into a working mine (‘Wireless: No More Tedious Monotony’ 1926). The ocean was perhaps the most challengingly liminal zone, resistant to human habitation and a barrier to urban settlement. During the 1920s however, the harbor was being transformed into an economically useful space for territorial expansion (Steinberg 2019), and radio was its eager earwitness.

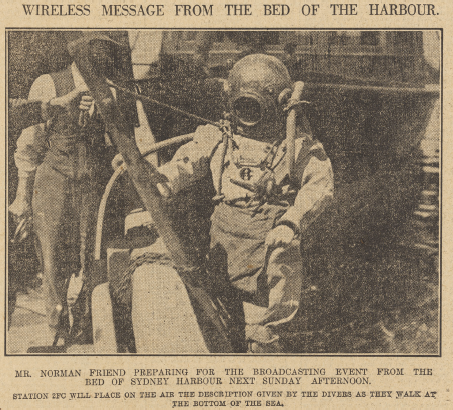

A ‘daring’ underwater broadcast in late 1925 signalled the harbor as a space that needed to be investigated radiophonically (Figure 4). Mechanically-assisted excavation and electronic communication came together on December 6 when the NSW Public Works Department (NSW PWD) sponsored a ‘Special Evening Transmission’ from Clontarf beach, near the Spit. The broadcast, hosted by commercial radio station 2FC[1], publicised complex and expensive (costing 3 million pounds, or equivalent to around 250 million AUD in 2019) underwater tunneling work that the State Government was completing around that time in the area (‘Wireless Message…’ 1925).

An article in published on December 4 in the rural NSW town of Wagga Wagga’s Daily Express explained that there would be 18-strong crew involved in the broadcast, including 4 broadcasting officers, and that unless “something goes wrong with the air, pipes and other connecting lines with the surface”, as an outside broadcast the radio event was technically possible (‘Broadcasting Divers’ 1925). Each diver would have “a telephone fitted in his helmet, so that every word he speaks will be passed along a wire to the surface, thence carried to the broadcasting station at Willoughby [2FC’s transmitter around 4kms away on the western edge of Middle Harbour], amplified and placed on the air” (‘Broadcasting Divers’ 1925). How the underwater scene would actually sound was a source of fascination:

The conversation of the divers with each other will be clearly audible to listeners, and although an encounter with a shark would be dangerous, many listeners will no doubt hope that such an occurrence will form part of the programme. The swish of a shark’s tail and the gnashing of his teeth have never yet been heard by radio.

(‘Broadcasting Divers’ 1925)

The two-and-a-quarter hour underwater feature began with “The Area 17b Sydney Military Band (conductor Mr. H. J. Glasby)” playing from divers’ punts located on the harbor, and interspersed technical commentary on the tunneling project with music performed by the band. In what the station believed to be “the first underwater broadcast in the Southern Hemisphere… actual descriptions [were made] of deep-water scenes as seen by [diver] Mr George Jack and [Sydney university marine biologist] Mr Norman Friend” (‘Farmer’s Service…’ 1925). Published accounts from listeners mentioned not just the musical and informational content of the program itself but reported the incidental sounds of the breathing apparatus from under 70 feet (20 metres) under the surface of the harbor as deeply affecting (‘Heard Them Breathe’ 1925).

Narrating incredible visions of underwater jungles of seaweed and reefs and dramatic stories of battles between sharks, all negotiated through precarious breathing apparatus and awkward diving suits, the underwater scenes that the observers described were portrayed as both a beautiful and dangerous world that only professional divers and biologists had access to, but one that would soon be tamed by modern engineering (Friend 1926; Elias 2019a; Elias 2019b). When the loudspeakers set up on the site worked briefly and then ‘went dumb’ when their batteries ran out, according to the Daily Telegraph’s reporter on the scene “onlookers [were] rewarded by a really thrilling incident” that made visible the dangerous work that the divers were doing under the surface:

Without warning the diver’s huge bulk shot to the surface on its back, fifteen feet away from the guide rope on the punt. At first one felt alarmed for Mr. French’s [sic] safety. Then one wanted to, laugh, as, indeed, everybody did, when it was realised what had happened. Mr. French had lost his hold of the guide rope, and his suit, being full of air, he rose to the surface, where he bobbed about as helpless as a bottle on its back. The situation became more comical still when the attendant at the ropes drew him alongside, and pressing his right foot into the diver’s middle, gradually succeeded in submerging him, while another attendant guided the diver’s hand to the rope adjoining the ladder. Mr. French was then lowered down again about 10 or 15 feet, and kept there for ten minutes until the process of decompression. Beyond a slight headache, Mr. French stated later that he was all right, and had gained much useful information regarding the harbor bottom and the marine growth along the sewer pipes. His one regret was that on coming up so suddenly he had lost a bag of marine specimens which he had collected. Mr. Jack came up without mishap, made his report to the broadcasting station, and a brass band played while the gathering dispersed.

(‘On Harbor Bottom’ 1925)

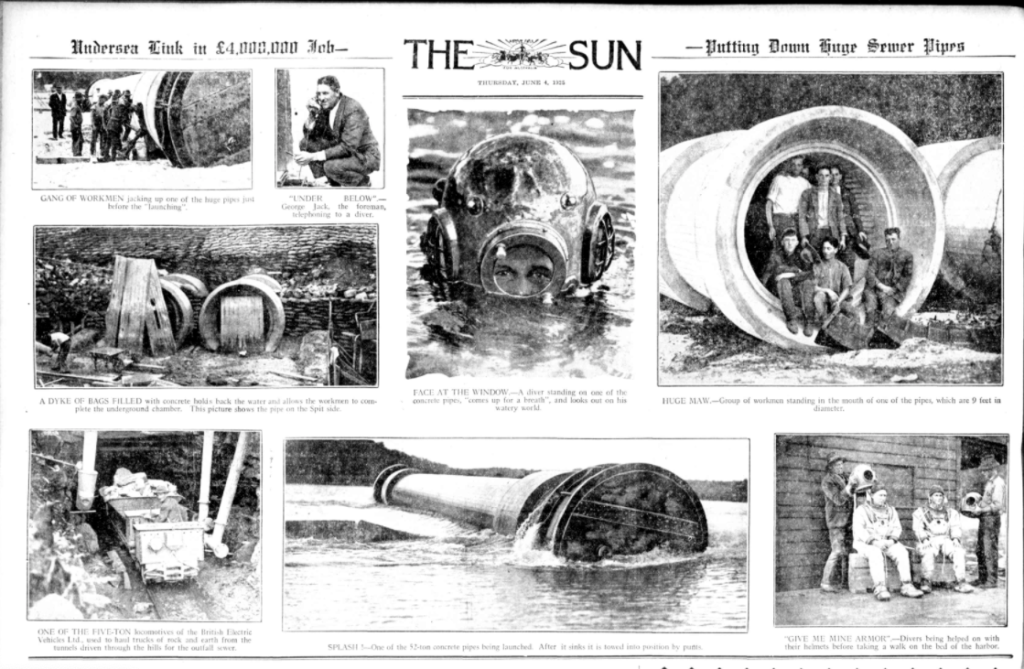

Newspaper reports of the broadcast emphasized the technical aspects of the project. Many did not explicitly mention the purpose of the tunneling itself, but rather the novelty for radio listeners of experiencing an underwater broadcast (for example, ‘Farmer’s Service’ 1925). The Daily Telegraph’s reporter eventually disclosed Jack as “diver-in-charge of the laying of the huge pipes across the Spit for the northern suburbs ocean outfall sewer” (‘On Harbor Bottom’ 1925). These pipes were part of a series of sewage tunnels that still cross the harbor, known as the NSOOS, constructed by the NSW PWD during the mid-1920s (Figure 5). This network of tunnels, connected by now heritage-listed infrastructure including Art Deco pumping stations and aqueducts (Office of Environment and Heritage 2000), were designed to carry waste within a 400 square kilometre urban watershed, reaching from Blacktown 50kms away in Sydney’s west, to Summer Hill 25kms away in the south and Narrabeen 14kms north, all heading towards a massive ocean outfall of untreated sewage (and other pollutants) at Blue Fish Point at Manly (‘Huge Sewer’ 1925; ‘Northern Suburbs Sewage Scheme’ 1925). Like the tunnels constructed for the electrification of Sydney’s tram network (Morgan 2018), this tunneling project was proudly promoted by the State government, who were attempting to cohere the city into a singular, modern identity by bringing transport and sanitation to the ever-expanding Sydney suburbs.

The NSOOS scheme has had a controversial legacy, and has been the source of much ecological damage to the coastal ecosystem. By setting the pattern for putting polluted water into the ocean, it was the impetus for putting waste further offshore, with deep-sea outfalls 2-4kms off Sydney’s coast built during the early 1990s, still dumping sewage and toxic chemicals directly into the Pacific Ocean (Beder 1992). On the 25th anniversary of the deep-sea outfall project in 2016, concern for the ecological impact of these massive transfers of pollutants and water that could be reused was trumped by putative social and economic value. The benefit of shifting ocean outfalls offshore was costed by an economic consultancy at 2 billion AUD since 1990, calculated by estimating impacts such as increased property prices, sick-days avoided by workers who might swim at polluted beaches and associated tourism and migration upticks for Sydney’s ‘brand value’ (Deloitte Access Economics 2016: 31-32). Little was said in this report about the impact of this human-created pollution on broader marine systems beyond the coastline and Sydney’s ‘branded’ beaches. Environmental scientists continue to call for a national re-examination ocean outfall schemes, and argue that the recovery and treatment of waste water is an urgent imperative in mitigating the effects of climate change and decreasing environmental stress on marine ecosystems (Wright et al. 2019).

As television encroached on radio’s monopoly of mediated explorations of the harbour, by the end of the 1940s radio turned away from live, outside broadcast to prerecorded, scripted documentary features. A feature by D’Arcy Niland, novelist, scriptwriter and husband of Sydney’s great biographer, Ruth Park, produced a radio documentary for the ABC’s light entertainment network in 1949, entitled ‘Ghosts Along The Quay’. Focused on the work of model ship builder Cyril Hume, the documentary retold the stories of famous old clipper ships in Sydney Harbour (Hume and Niland 1949). The 2UW radio event of 1937 (discussed in part 1 of this essay) was thus bookended by radio’s transformation from a medium of aural attractions of the 1920s to a more essayistic, less modern and therefore nostalgic, cultural form by the end of the following decade.

References

2UW (1937, June 25). Top Speed Express to the Magic Land of Make Believe. The Wireless Weekly: the hundred per cent Australian radio journal. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-707706170

‘Anniversary Cruise of 2CH Jolly Boat’ (1941), Wireless Weekly: The Hundred per cent Australian Radio Journal, January 25 (4): 29. Available from http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-681473775

‘Broadcasting Age in Sydney: In Line With World’s Best’ (1924), Evening News. January 8: 10. Available from https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/119198324/12600458

‘Broadcasting’ (1937), The Sydney Morning Herald. October 30: 10. Available from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article17420423

‘Broadcasting Divers’. 1925. The Daily Express. December 4: 3.

‘Farmer’s Service: Call Sign, 2FC; Wave Length, 1100 M.’ (1925), The Sun. December 6: 4. Available from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article223927065

‘Harbor Outing for 2UW Children’ (1937), The Cumberland Argus and Fruitgrowers Advocate. October 14: 14. Available from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article106163626

‘Heard Them Breathe’ (1925), Evening News. December 9: 11. Available from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article126132268

‘Mr Norman Friend preparing for the broadcasting event from the bed of Sydney Harbour’. (1925). The Sydney Morning Herald, December 2: 18. Available from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-page1218200

‘On Harbor Bottom: Broadcasting Feat’. (1925,). Daily Telegraph, December 7: 7.

‘Radio Programmes: Sydney Harbour Documentary’ (1949), Newcastle Morning Herald and Miners’ Advocate May 31: 5. Available from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-page10088326

‘Wireless Message from the Bed of the Harbour’ (1925), The Sydney Morning Herald December 2: 18. Available from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article16258279

‘Wireless News: Underwater Broadcast’ (1926), The Armidale Chronicle. October 16: 11. Available from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article187949076

‘Wireless: No More Tedious Monotony’ 1926), The Sydney Morning Herald. March 8: 5. Available from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article16263504

‘Huge Sewer. Northern Suburbs. To Cost £3,000,000. Good Progress.’ (1925). Sydney Morning Herald. January 16: 8. Available from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-page1223302

‘Undersea Link in £4,000,000 Job — Putting Down Huge Sewer Pipes.’ (1925). The Sun, June 4: 20. Retrieved from https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/224053451#

Attenbrow, V. (2009). Aboriginal placenames around Port Jackson and Botany Bay, New South Wales, Australia. In H. Koch & L. Hercus (Eds.), Aboriginal Placenames. Canberra: ANU Press.& Aboriginal History Incorporated.

Beder, Sharon. 1992. ‘Getting into Deep Water: Sydney’s Extended Ocean Sewage Outfalls.’ in Pam Scott (ed.), Herd of White Elephants: Australia’s Science & Technology Policy (Hale and Iremonger: Sydney): 62-74.

Davies, A. (1991), Sydney exposures: through the eyes of Sam Hood and his studio, 1925-1950, Sydney: State Library of NSW.

Deloitte Access Economics. 2016. Economic and social value of improved water quality at Sydney’s coastal beaches. (Sydney Water: Sydney, NSW).

Elias, A. (2018), The floor of Sydney Harbour: A cultural history. Sydney Environment Institute. Available from https://sei.sydney.edu.au/opinion/floor-sydney-harbour/

Elias, A. (2019a), Coral Empire: Underwater Oceans, Colonial Tropics, Visual Modernity, Durham: Duke University Press.

Elias, A. (2019b), ‘Alien Harbour: Frank Hurley, Jules Verne, and the Early Dress-divers of Underwater Sydney’, Australian Historical Studies, 50 (2): 212-234.

Friend, N. B. (1926), ‘Under the Sea with Wireless’, The School Magazine of Literature for our Boys and Girls, June 3 (5 Part 3 for Classes 5 & 6): 84-85. Available from https://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-77388001

Gunning, T. (1986), ‘Cinema of Attractions: Early Film, Its Spectator and the Avant-Garde’, Wide Angle, 8 (3-4): 63-70.

Gunning, T. (2006), ‘The Cinema of Attraction[s]: Early Film, Its Spectator and the Avant-Garde’, in Strauven, W. (ed) The Cinema of Attractions Reloaded, 381-388. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

Hume, C. and Niland, D. A. (1949), ‘Ghosts Along The Quay’. In: Ruth Park and D’Arcy Niland further literary papers, 1930s-1993 BOX 11. 447336 MLMSS 8075. State Library of NSW.

Morgan, B. (2018), Visualising the Invisible: The Original Sydney Harbour Tunnel. Sydney Environment Institute. Available from http://sydney.edu.au/environment-institute/blog/visualising-invisible-original-sydney-harbour-tunnel/

Steinberg, P. (2019), Ocean-Space. Current Projects. Available online: https://philsteinberg.wordpress.com/research/ocean-space/

Office of Environment and Heritage. (2000). Northern Suburbs Ocean Outfall Sewer (NSOOS). NSW State Heritage Register. Available from https://www.environment.nsw.gov.au/heritageapp/ViewHeritageItemDetails.aspx?ID=4570286

Wolfe, C. Seeing the Better City: How to Explore, Observe, and Improve Urban Space. Washington: Island Press.

Wright, Ian, Andrew Fischer, Boyd Dirk Blackwell, Qurratu A’yunin Rohmana, and Simon Toze. 2019. ‘Australia’s pristine beaches have a poo problem.’ The Conversation. 17 June. Available from https://theconversation.com/australias-pristine-beaches-have-a-poo-problem-116175.

[1] 2FC was owned by the ‘Farmer and Company’ retail empire at the time, and had been broadcasting from their downtown Sydney flagship store since 1924, with their 5000 watt transmitter at Willoughby linked by landline (‘Broadcasting Age in Sydney: In Line With World’s Best’ 1924). The station was later taken over in the early thirties by the Australian Broadcasting Commission, the precursor to the current public broadcaster, and is now known as the Australian Broadcasting Corporation’s ‘ideas network’, Radio National.

About the Author

Dr Justine Lloyd – is a senior lecturer in sociology at Macquarie University. She researches the links between history, space and place. Her book on intimate geographies of media entitled Gender and Media in the Broadcast Age: Women’s Radio Programming at the BBC, CBC, and ABC has recently been republished in paperback by Bloomsbury Academic. She has also has recently co-edited a special issue of Feminist Media Studies on the theme of “Transnational Media and Gender” with Dr Jilly Boyce Kay, and is co-editing a forthcoming special issue of Space and Culture on “Critical Perspectives on Sites of Conscience” with Dr Linda Steele. A virtual special issue linked to the Space and Culture collection is available via the journal’s website.

Thanks to the members of the Transnational Media Histories project, including Dr Hans-Ulrich Wagner, Dr Virginia Madsen, Dr Chris Muller, and Professor Bridget Griffen-Foley as well as the State Archives and Records Authority of NSW, especially Rhett Lindsay, Archivist for assistance on tracing the connections between the broadcast and the Public Works Department. Special thanks to Chris Muller for his comments on an early draft.

See also Harbour Cities: Sounding Sydney Harbour: radio explorations above and below the surface: Part 1