Chen Xinsheng, Shanghai

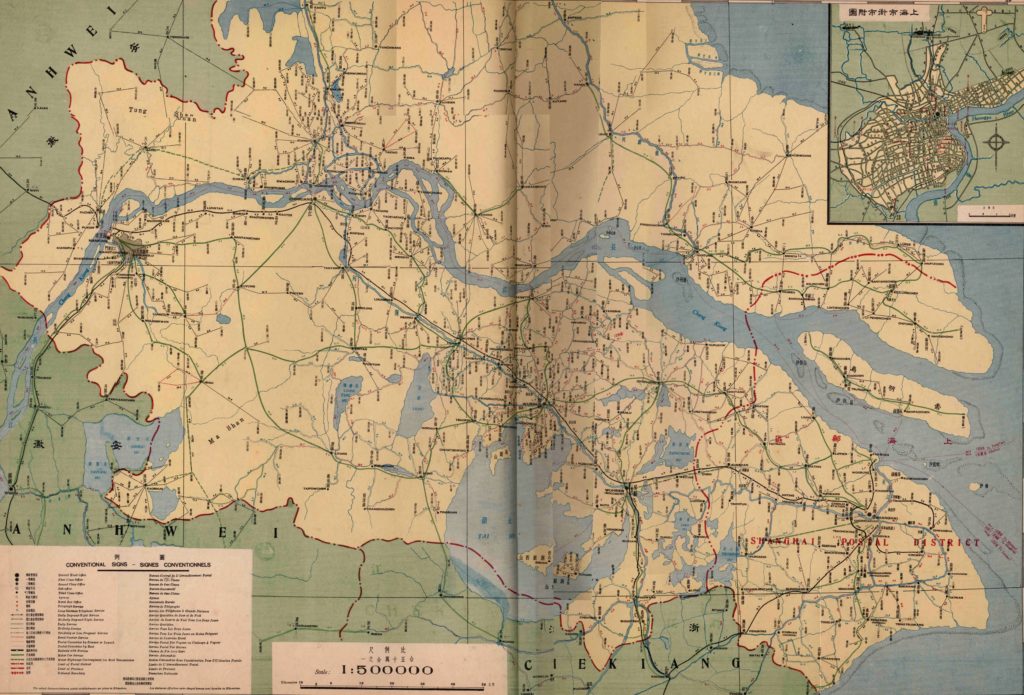

Figure 1. Nanking Directorate General of Posts. Postal map of Jiangsu—Shanghai postal district, 1935, photograph.

Image courtesy of the Center for Geographic studies of Fudan University, Shanghai.

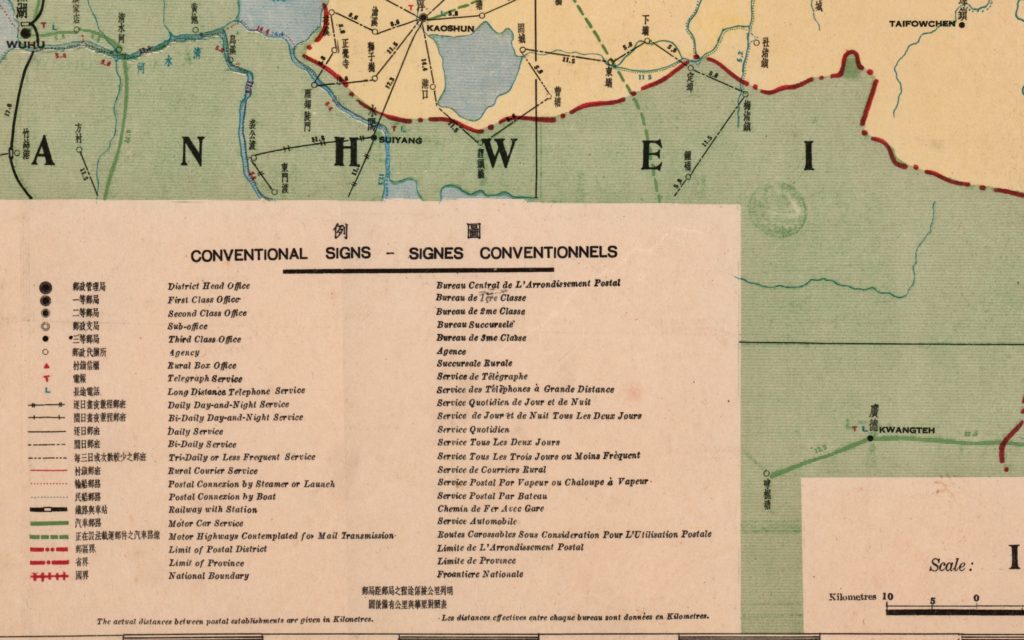

Postal connections by railway, steamer, launch, boat, motor car… Something new is visualized on this map. This postal map of Jiangsu—Shanghai postal district, which was published in the China Postal Atlas of 1935, shows postal establishments in this district (Figure 1). As can be seen from the map, various types of regular routes were set up to connect cities and villages among the district. According to the load capacity of each route, stations were divided into seven levels: the top level, District Head Office, which was situated in Shanghai, the biggest port at that time in China, while the following levels were dispersed around Shanghai: the first-, second- and third-Class Offices, Sub-Office, Agency and Rural Box Office. Within the postal network by routes and stations, mail correspondence became therefore a consideration of the consumption of time, which is also showed on the map: Daily day-and-night service, Daily Service, Bi-daily Service, Tridaily and Less Frequent Service (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Nanking Directorate General of Posts. Postal map of Jiangsu—Shanghai postal district, 1935.

Detail of ‘Conventional Signs’, photograph.

Image courtesy of the Center for Geographic studies of Fudan University, Shanghai.

The map reveals the postal revolution which had swept the whole country in late imperial China. The first postal atlas was released in 1903—almost ten years after the establishment of the official Chinese postal system. By 1935, this atlas had been revised four times to catch up with this modern project. The atlas contained one national postal map and 30 postal district maps. “It is of a necessity for every citizen to keep this book at home [为社会人士一致需求之图籍]”, commented Zhu Jiahua in 1935 as the head of Ministry of Transport in the Republic of China, when this fourth version of the Atlas was published (Zhu, 1935). This favorable remark proved the increasing importance of the postal system at that time. Although the Chinese national postal system was developed relatively late in comparison to western countries, it met a high speed of expansion and soon became one of the most important actors for social and cultural lives in early modern China.

Let’s move to the history behind the map: the rise of the national postal system was related to a new wave of urbanization since the second half of the 19th century, the last period of imperial China. The emergence of commercial ports like Shanghai witnessed a boost in international trade. To pursue treasures in these unprecedented markets, millions of people moved from various areas of China into new port cities. This large-scale immigration then created a strong demand for long-distance interpersonal communication, which soon prompted a common appeal of the national postal system.

The building of the national postal system proved to be a long and hard process. Since there were, for centuries, already private postal networks like Min Xin Ju Institutes [民信局] which worked as regional commodity transport, the government was reluctant to engage into transportation markets—in traditional political culture, it was not suitable for an emperor to compete with people in markets [天子不可与民争利]. The turning point arose, interestingly, due to the influence of Robert Hart, an Irishman who served the Chinese emperor as head of General Administration of Customs. Advocating for a national postal system over 30 years, Robert Hart finally got authorization from the emperor and soon set up the Imperial Post Office in 1896. From that point onwards, the Chinese postal system expanded rapidly from cities to villages, from ports to inland regions, from the eastern to the western part of China. It was undoubtedly difficult to set up a postal system in such a large land with highly complicated geography. As can be verified from the map, various types of vehicles, especially industrial transports like railway, motor car and steamer, were applied into a unitary network to overcome geographic factors and keep the system working steadily (Figure 3). Even so, in the final days of Imperial China, the postal system had already covered most of the country and the government even decided to dissolve its military network, Yi Zhan [驿站”], and officially adopted a national postal system instead.

Figure 3. Nanking Directorate General of Posts. Postal map of Jiangsu-Shanghai postal district, 1935.

Detail of Shanghai on the map, photograph.

Image courtesy of the Center for Geographic studies of Fudan University, Shanghai.

Different from the so-called ‘mass media’ like newspapers, the postal system can be regarded as a type of networked media, which means a decentralized form of interpersonal communication (John, 2009). These characteristics of the network determined its impact on existing hierarchies and its potential to reorganize society into a more democratic and diversified structure.

From this perspective, the postal map showed as above, can be seen as a proper object to exemplify how a networked postal system made a difference to Chinese society: maps visualized, without limitations of access, the operation and its service details (e.g. consumption of time, postage, etc.) of the postal system, bringing the benefits of remote communication into users’ daily lives. With the empowerment of the postal system, users were transferred into nodes of the national—later global—network, and their social relations were reshaped as a further consequence. I illustrate three key aspects of this argument in the following section:

Firstly, with the popularization of remote communication, individuality, as a basic mode of modern civilian, was cultivated in Chinese urban context. As mentioned earlier, the general background of the Chinese postal system related to the huge needs of immigrants in new ports. Unlike other cities in China, those new ports were composed mainly by immigrants who lived far away from their hometowns and were trapped into an urban social environment—as Georg Simmel said, a society of strangers. As a result of that, the postal network not only provided those groups with a stable channel to keep contact with their friends and relatives, but also afforded their individualized lifestyles as well. It soon became a common experience for those who lived in ports to dealing with public and private affairs by mail instead of presence. A typical beginning to daily affairs for the petty bourgeoisie in Shanghai was to reading letters, which had already taken out from envelopes by a servant, and then making decisions on daily schedules. As more and more people became accustomed to mail correspondence, this independent manner of working and living accelerated the process of individualization and changed the basic units of Chinese society from kinship-based family to modern citizenship.

Secondly, a virtual public space was operated by those networked individuals. Those who mailed each other regularly could not only make daily arrangements but also exchange their opinions towards social phenomena. For students in schools and universities or social corporations, exchanging mail was a common way to discuss cultural and social issues by mail. Newspapers and magazines published special columns for pen-pals to express their opinions. Furthermore, letters from celebrities were edited and released by the press to generalize public debates. These practices, in consequence, formed a pattern of public opinion to promote modern thoughts in China at that time, despite the lack of physical public spaces for doing so.

Thirdly, the social structure formed by the postal system reconfigured the modes of urban governance. Although local governors in imperial China still kept the authority from the emperor, they faced new challenges to this authority activated by the postal system. As a new platform for people to express their appeals to local governors, the postal system revealed “hidden voice of people” for governors, who lost the privilege of keeping distance within the network and had no other choice but to respond to them. This mode of governance provoked people’s consciousness of supervision, which in turn attracted various report letters on their conduct. However, as these letters were delivered by postal system, a large part of them were anonymous letters and the words proved to be far from objective. As a result, urban governors, who needed to identify the authenticity of this increasing volume of such letters to avoid being misled, were trapped into passive positions. A political culture of civil supervision, which didn’t exist in China before this point, was carried out at this stage and set a democratic model for the republican regime—no wonder that the postal system was later praised as “spirit of the republic” in post-imperial era of China (Cheng, 1970).

The map also reveals the connections between cities via postal routes. However, it could also be said that cities themselves, viewed from a media respective, were reshaped—or to some extent ‘created’—by the postal network. In recent years, studies of Chinese type of modernity have started to emphasize the effect of material culture, for which the postal system could be seen as an excellent example: by creating a networked social structure, the postal system as media contributed to the modernization of Chinese urban society.

References:

Cheng, Y. W. (1970). Postal communication in China and its modernization, 1860-1896. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University East Asian Research Center.

John, R. R. (2009). Spreading the news: The American postal system from Franklin to Morse. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

Nanking Directorate General of Posts (1935). China Postal Atlas. Shanghai: Supply Department, Directorate General of Posts.

Zhu. J. H. (1935). Preface. China Postal Atlas. Shanghai: Supply Department, Directorate General of Posts. pp.1-3.

About the Author

Chen Xinsheng is a Ph.D. candidate from the Center of Information and Communication Studies at Fudan University. As a researcher, he has a strong interest in how various types of media ‘determined our situation’ in historical China. His doctoral thesis focuses on how the postal system changed the lives of urban Chinese in early modern China (1896-1949). He also pays close attention to the development of digital media practices (like Mobike, Tik-Tok etc.) in today’s China.