Willa McDonald, Sydney

Soong Mei Ling – “To the Women of the World”

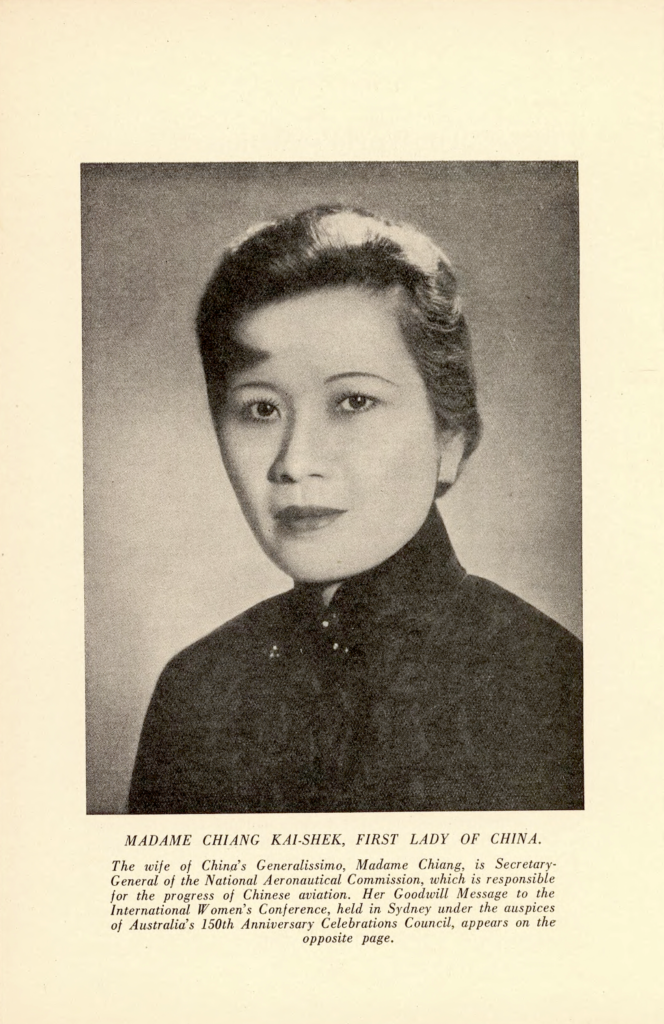

Image courtesy of National Library of Australia, https://catalogue.nla.gov.au/Record/1639912.

Pao’s promotion of collective security, through an alliance between China and Australia in the face of rising Japanese militarism and an unstable Pacific, is reinforced by the inclusion at the end of the pamphlet of Soong Mei-Ling’s message of goodwill to the “World’s Women” through the International Women’s Conference (Figure 3). While Pao’s pamphlet was well received and comprehensively covered in the small attention it drew from the press, Soong’s message attracted more (and more critical) attention. It was called “This Changing World: Women’s Part in It”. At first glance, it seems curious that Soong’s message to mark the Sesquicentenary makes no real reference to the celebration, nor to women of Chinese heritage in Australia. The omission underlines the offensiveness to China of the White Australia policy and its impact on Australia’s ethnic diversity. Pao directly addresses this in the pamphlet, stating:

[T]he Australian government and people know full well that we have no resentment against any economic policy which is designed to preserve Australian national homogeneity, but we of course deplore the sometimes humiliating procedure of restriction, the nature of which is, even in many Australian eyes, contrary to the new concept of the international comity of nations…

Soong-Mei Ling, “Message from China”. (1938, February 5). Argus, p. 29.

While Australia at the time still had sizeable Chinese communities in all its states, the policy had frozen these into a steady decline. The number of Chinese residents had dropped by nearly two-thirds in the years since Federation. Very few of those remaining were women. Pao’s pamphlet quotes the 1933 census to show there were around 4000 people of Chinese nationality residing in New South Wales, with by far the majority male. Only 77 of these residents were women (Pao, pp. 13-15). Besides Australia’s racially discriminatory legislation, disparity in numbers of resident Chinese is also explained by traditional Confucian family structures which prevented women from being independently mobile. When men migrated to become traders, indentured labourers, or to join the search for gold in the nineteenth century, Chinese wives rarely migrated with their husbands (Klamp, 2013). Although the gender disparity shown in the census largely disappears when the numbers of Australian-born women of Chinese heritage are examined, the overall numbers of resident women of Chinese heritage were still very low. The census figures show there were roughly even males (727) and females (640) in 1933 (Pao, pp. 13-15).

Rather than including Australia’s Chinese communities in her message, Soong took a different approach. She began by asking the women of the world to turn their attention to the difficult circumstances experienced in China in the midst of the Sino-Japanese War (“Message from China,” 1938). The message described the part Chinese women were playing to alleviate some of the suffering in a war which had already seen Beijing, Shanghai and the capital Nanjing fall to the Japanese. It urged “a more determined effort by women to outlaw war and to alleviate the misery and affliction occasioned by the ruthless Japanese aggression in China” (Pao, p. 59). The message was read to conference delegates on the last day of the conference by two women from Shanghai: Mrs Fabian Chow, “a journalist on the staff of the principal British-owned newspaper” in that city (“Message from China,” 1938), and Mrs Elsie Lee Soong of the Chinese Women’s Club.

Soong Mei-Ling, China’s First Lady, was blunt in her language and intent, presumably to penetrate reader indifference among her international audience. She criticised conferences as ineffective, calling instead for “practical action”:

Let us say “mea culpa” and not blame the rest of the world for what is happening around us. If there has been indifference in our hearts, or too strong a personal ambition or a tendency to follow the line of least resistance, the beaten track of international conferences, meetings and more meetings, at which long strings of beautiful words are said but very little practical work ever accomplished—let us confess that this is not the way to save the world.

Pao, p. 64

Soong used the occasion to publicise the New Life Movement which had been introduced in China in 1934 by her husband Chiang Kai-shek and the Kuomintang or Nationalist Party, and which she represented as its public face (Chiang, 1934). Blaming corruption and moral decadence for continued crises in the Republic of China—a country weakened by Western imperialism, Japanese militarism and domestic factionalism—the Kuomintang leadership launched the New Life Movement as a way of revitalising China (Dirlik, 1975). The movement mixed elements of Neo-Confucianism with Christianity, authoritarianism and opposition to Communism, and was intended to unite the country under this single ideology that would lead to social and moral renewal (Liu, 2013). Soong called on the conference delegates to play a part in its international spread, targeted at globally “raising the standard of living, increasing education and creating a ‘new spiritual life’” (Pao, p. 64).

Soong’s message focusses on personal reflection and responsibility. She asked that the participant organisations and their members “devote a period every day to international thought. Ask yourselves what part you are to take each day to stop this changing world, and you must achieve good”. She also called for the creation of “a vacuum round any aggressor state that dares to endanger the peace of the world”. And she asked women “to cut the sinews of war and take profit out of war…let every one of us resolve not to spend a penny that might wander to the aggressors’ war chest” (Pao, p. 64).

Soong’s call for an international New Life Movement, despite its political intent, generally was not the subject of the Australian media coverage, but nor was it really aimed at Australian audiences. The message was clearly targeted at the international conference delegates, if not also domestic Chinese audiences, to whom she wanted to convey the significance of the New Life Movement. What did draw attention was Soong’s criticism of the conference itself as a potential means to achieve effective results. Her plea for peace-making and her publicity of the New Life Movement barely rated a mention. The Sydney Morning Herald, for example, quoted a substantial section of the message under the headline, “Conferences not the way to Save World, Madame Chiang Kai-shek’s opinion” (“Conferences,” 1938). The exception was Melbourne’s Argus which,while it described the message as the conference’s “most dramatic incident” at least included the paragraph referring to the New Life Movement, although without explanation (“Message from China,” 1938).

Transnational Entanglements – Women’s Work:

International conferences have long been used by women to build transnational networks between women and women’s organisations with the aim of influencing states and putting human rights onto government agendas (Coltheart, 2005). The first international women’s conference was held in Paris in 1878 and from that time they were a feature of twentieth century feminist politics culminating in the United Nations sponsored Fourth World Conference on Women in 1995. While championing themselves in the first half of the twentieth century as uniting and speaking for all women no matter what colour, creed, nation or class (Rupp, 1996), in reality they operated primarily across English-speaking countries, mainly attracting educated, white, middle class women as delegates. Because of distance and the difficulties of pre-war travel, those who participated generally had to have sufficient social standing to have the time and money to attend although there were also women who took part who earned their living and others who attended using funds raised from supporters (Coltheart, 2005, Rupp, 1996).

The Sydney-based activist Jessie Street, for example, was not only part of the International Women’s Conference in Sydney in 1938 (and in her capacity as vice-president of the Australian Federation of Women Voters an organiser of a follow-on national conference held immediately afterwards), but travelled to Geneva later that same year to attend the annual meeting of the transnational women’s organisations arranged each September to coincide with the General Assembly of the League of Nations. When the Treaty of Versailles was being formulated in 1919, the International Council of Women had lobbied for the Covenant of the League to explicitly allow for equal representation of women on the Secretariat. As an international federation of member states, the League enabled women to move beyond petitioning only their national governments to being able to work transnationally for international rights and standards for women and workers, for example through the International Labour Organisation in the 1920s (Coltheart, 2005). Research has demonstrated the success of such world-wide carriers of global culture as the League in adding legitimacy to local reform agendas, helping to define and embed them in the policies of individual nations. (Paxton, Hughes, & Green, 2006).

When Street visited Geneva in 1938, her second visit to join the annual meeting, there were eight transnational organisations of women with their headquarters in the city, which she estimated represented a total of 50 million women from around the world. As Lenore Coltheart notes, these organisations and their branches, had many functions:

They were ‘outdoor parliaments’ where women like [Vida] Goldstein campaigned for political equality in international fora of rallies, lectures, conferences, executive meetings, and newsletters. They were travel agencies, particularly for the distant Australians, providing advice and arrangements for Goldstein and others such as journalist and labour reformer Alice Henry and writer Miles Franklin. They were training institutes, trading exchanges, lobbies, fundraising foundations and friendly societies.

(Coltheart, 2005, pp. 183-184).

Street made the most of her trip, bookending it with extended travel during which she researched reform issues and networked her way through the USSR, Europe and Britain, also addressing meetings in England and the United States on her twin causes of internationalism and feminism before returning home (Coltheart, 2005).

In this context, the dismissal of the value of women’s conferences by Soong must have been jarring, perhaps helping to explain the focus of the newspaper coverage. Essentially ignored by the news sections, the reports of Soong’s message and of the conference itself mostly ran in the women’s pages of the metropolitan newspapers. In 1930s Australia, and indeed across the Anglophone world, women were usually kept out of the news pages of the print media and corralled onto specialist sections where they were confined to “the deadly, dreary ruck of long dress reports and the lists of those who ‘also ran’ at miscellaneous functions” (Cox-Taylor, 1912). As Patricia Clarke (1988) observes, while the women’s columns and pages, designed to be an avenue for marketing products relating to the domestic sphere, increased some women’s chances of permanent employment, they were overall a backward step for women’s professional development in journalism. Broader society lost out, with the work of the journalists tending “to reinforce complacency in their women readers and to shield them from issues of some significance” (Clarke, 1988, p. 4). This too may have been a factor in the limited coverage accorded the conference.

The Age, another Melbourne paper, provided the most comprehensive report of Soong’s message by also covering the speech of Eleanor Hinder, an officer of the Shanghai Municipal Council. Hinder used her talk to discuss the situation of the “modern Chinese woman”. She related the difficult circumstances of women working twelve-hour days in China’s cotton mills, while praising the work by Chinese women over the previous decade to insist on equality with men resulting in the introduction of the principle of equal pay for equal work regardless of gender, the right to equal education opportunity for women, the prohibition of enforced marriages by parents, easier access by women to divorce, and the dropping from the criminal code of punishments of unfaithful wives (“Women in India and China,” 1938).

The most critical reaction to Soong’s address, and indeed of the whole conference, was that of the Australian Women’s Weekly, produced in Sydney. The editor, Alice Jackson, wrote the report which appeared on Saturday 12 February. She mostly concentrated on the outfits worn by the women, while very briefly and with snide humour summarising in a sentence or two the speeches of some of the main dignitaries. These were mostly the wives of society’s leading men, including Lady Gowrie, Lady Galway, Dame Maria Ogilvie Gordon, Lady Huntingfield and Dame Enid Lyons, as well as the noted feminist and chair Mrs Bernard (Mildred) Muscio. Jackson pointed out the affluence of the delegates who arrived in “comfortable Rolls to Fordish models, at worst, first class in the train… mostly matronly, at the stage when the children are well off the hands, married, or in good jobs.” She finished the report with another reference to social and class divisions. “Outside, torrents of rain… taxis rapidly gobbled up… Chauffeur descends from luxurious limousine with huge umbrella and escorts one lady back to same… From the waiting rest a sigh of envy. From one, the trenchant comment: As Mrs Muscio says, ‘All women should be genuine democrats’!” (Jackson, 1938a).

Jackson followed her article up a week later with an editorial that said of the conference, “Judged on any standards, except possibly the social, it was a disappointment. But its failure caused little stir among women. This confirms what competent observers have often pointed out – that Australian women are not keenly interested in what is known as the Feminist Movement with its implications of sex rivalry.” Jackson instead, worried by a falling Australian birth rate, called for a campaign to convince women of the “joy and glory” of motherhood (Jackson, 1938b). Whether or not Jackson’s criticisms were widely shared is unclear, as there was no subsequent commentary in the mainstream newspapers of the day.

Conclusion

Pao’s pamphlet and Soong’s message are exercises in transnational soft power diplomacy, signalling a multiplicity of messages to Australian, Chinese and international audiences with the aim of community building within and between nations. In their different ways, the pamphlet and message reflect the diplomatic and political measures employed by China at the time to enhance relations with Australia, improve its international standing and, on the Chinese domestic front, to unite the Chinese people under a singular ideology for the political survival of the Nationalist government in the late 1930s as well as cultural, social and moral reform. To the Australian audience, Pao’s primary intention in producing his pamphlet is to promote trade, with economic co-operation as a forerunner to an alliance with a unified and independent China in order to secure a stable Pacific region, but he also uses his pamphlet to counter racism against the Chinese, downplay any economic threat from China and advocate for a relaxing of the White Australia Policy.

Without Pao’s pamphlet the complete record of Soong’s goodwill message would not be available in Australia and we would not have the intriguing glimpse it provides into the transnational use of public diplomacy in the building of shared cultural space within and between China and Australia. By including Soong’s goodwill message to the International Women’s Conference, Pao endorses the New Life Movement and its campaign to unite China behind Chiang Kai-Shek and the Chinese Nationalist Party through the promotion of cultural and moral reform. He also in this way draws women into the Sesquicentenary celebrations as well as the political process.

Soong’s message demonstrates the way such transnational conferences were used, not only for networking and sharing ideas but also to make political points. The inclusion of the conference in the Sesquicentenary celebrations at all is an indication of the strength of the women’s movement in Australia between the wars, at least among a certain class of educated women, and the importance of the entangled international networks between women that supported the conference and allowed it to happen. Its location in the harbour city of Sydney, most easily accessed by ship in 1938, enabled international participants including from India and China to attend in person, strengthening the transnational impact of the congress.

Finally, the overall lack of interest shown by the mainstream press in Pao’s pamphlet, together with the press’s defensive reaction to Soong’s message, signals some of the gender, class and ethnic divisions that marked the socio-cultural spaces of the fledgling Australian nation during those formative years between the two world wars and at the height of the White Australia Policy, also helping to delineate some of the entangled transnational context in which this moment in history took place.

References:

“Conferences not the way to save world: Madame Chiang Kai-shek’s opinion”. (1938, February 5). Sydney Morning Herald, p. 19.

“Message from China”. (1938, February 5). Argus, p. 29.

“Our historic day of mourning and protest. (1938, April 1). The Abo Call, p. 2.

“Women in India and China: Status reviewed at Sydney Conference”. (1938, February 5). Age, p. 13.

Anderson, B. (1983). Imagined communities: reflections on the origin and spread of. Nationalism. London: Verso.

Blainey, G. (1966). The tyranny of distance: how distance shaped Australia’s history. Melbourne: Sun Books.

Chiang, K. (1934). “On the need for a New Life Movement”[Speech]. Asia for Educators: An Initiative of the Weatherhead East Asian Institute at Columbia University. Primary sources with DBQs, China 1900-1950. Retrieved from http://afe.easia.columbia.edu/ps/cup/chiang_kaishek_new_life.pdf

Clarke, P. (1988). Pen portraits: women writers and journalists in nineteenth-century Australia. Sydney: Allen & Unwin.

Coltheart, L. (2005, May). “Citizens of the world: Jessie Street and international feminism”. Hecate. 31 (1): 182-194.

Cox-Taylor, M. (pen name “Valerian”). (1912, May 30). “A Woman’s Letter”. Bulletin, p. 22.

Dirlik, A. (1975). “The ideological foundations of the New Life Movement: A study in counterrevolution”. Journal of Asian Studies, 34 (4): 945–980.

Fitzgerald, S. (2008). “Chinese”. Dictionary of Sydney. Retrieved from https://dictionaryofsydney.org/entry/chinese).

Jackson, A. (1938a, February 12). “Sidelights on big Sydney conference”. Australian Women’s Weekly, p. 24.

Jackson, A. (1938b, February 19). “An editorial: our empty cradles” Australian Women’s Weekly, p. 10.

Klamp, A. (2013). “Chinese Australian women in white Australia: utilising available sources to overcome the challenge of ‘invisibility’”. Chinese Southern Diaspora Studies, 6, . 75-101.

Liu, Wennan. (2013). “Redefining the moral and legal roles of the state in everyday life: the New Life Movement in China in the mid-1930s”. Cross-Currents: East Asian History and Culture Review, 2(2), 335–365.

National Australia Day Council. (N.d.) “1938–The Sesquicentenary and the Day of Mourning”. Retrieved from https://ausdayold.siteinprod.com.au/australia-day/history/1938-the-sesquicentenary-and-the-day-of-mourning/

National Museum of Australia. (Updated 13 March, 2020). “Defining Moments: Day of Mourning”. Retrieved from https://www.nma.gov.au/defining-moments/resources/day-of-mourning

Pao, C.J. (1938). A Century of Sino-Australian Relations. Sydney: John Sands.

Paxton P. , Hughes M.M., & Green J.L. (2006). “The international women’s movement and women’s political representation, 1893–2003”. American Sociological Review, 71(6): 898-920.

Rupp, L. (1996). “Challenging imperialism in international women’s organizations, 1888-1945”. NWSA Journal, 8 (1): 8-27.

About the Author

Dr Willa McDonald – BA/LLB, PhD (Australian Studies) – is Senior Lecturer in Media at Macquarie University where she teaches and researches creative non-fiction writing and narrative journalism. A former journalist, she has worked in print, television and radio, including for the Sydney Morning Herald, the Bulletin, the Times on Sunday, ABC TV and ABC Radio National. She is currently writing a cultural history of colonial Australian literary journalism, and co-editing an academic collection on social justice and literary journalism, both for Palgrave Macmillan. She is the chief author of the Australian Colonial Narrative Journalism Database, now available on AustLit. Willa’s books are: Warrior for Peace: Dorothy Auchterlonie Green (2009, Australian Scholarly Publishing) and The Writer’s Reader: Understanding Journalism and Non-fiction (with Susie Eisenhuth, 2007, Cambridge University Press).

See also Entangled History and Transnational Context: Part 1 & Entangled History and Transnational Context: Part 2