I’m trying to work through worries about spatialization and ethical issues in Borat and Borat Subsequent. In his films, Sacha Baron Cohen lampoons Kasakhstan as the home and culture of his character Borat. In an interview he argued that inserting a fictional character into an actual situation is a new form of comedy. Ghada Chehade notes that given the fictional quality of the character Borat, the producers could easily have invented a fictional country of origin, a ‘Boratstan.’ However, across the fragmented series of gags and hoaxes the movie features, the protagonist’s homeland in Kazakhstan is a consistent reference point. He’s from Kazkhstan encountering America and Americans.

Why is it necessary to parody and stereotype a country (although the scenes of Kazakh village life were actually shot in rural Romania with paid villagers as extras), its culture and people in order to achieve Baron Cohen’s aim of exposing American anti-semitism and bigotry? The claims and portrayal of Kazakhstan and Kazakh culture are not only inaccurate but characterize it as backward, using a systematic series of taboos and breaches of ‘Western’ decorum associated with extreme patriarchy, anti-semitism and uneducated, unprogressive pre-modernity. Taboos – this is the root of the feeling of horror at many of Borat’s puns and word choices – to the extent that his victims are speechless at such gaucheness. Choosing an actual country may be related to the ‘legitimate’ air, Baron Cohen seeks to maintain in setting up his interviews with those have lampooned. In any case, the resulting publicity both drew sharp criticism from the government of Kazakhstan and increased tourism to the country by a purported ten times (BBC 2016).

A composite image of the fictional ‘Kazakhstan’ is created by the mashup of fictional segments in the Borat films, scenes or stunts in rural Romanian villages, gibberish presented as Kazakh speech and writing, and descriptions the protagonist Borat gives of his rural origins. It is notable that children are almost completely absent from any of the scenes in the films. This is clearly a one-dimensional portrait. Perhaps this constructed homeland could be called Kazakhstan but placed in quotes. This is a virtual Kazakhstan: Romania-as-if-Kazakhstan. This virtual country is more correctly a composite of Eastern European class and religious tensions that arose over the 19th and 20th centuries between Jews, Gypsies, peasants, Slavs, ethnic Germans partly as a result of divide and conquer strategies of the 19th century nobility that used these groups to oppress each other to maintain still-feudal social relations.

‘Kazakhstan’, then, is the homeland of every currently politically incorrect attitude and statement. Chief of these are public anti-semitism and a casual chauvinism that treats women as akin to livestock. Amongst other vices, the films orchestrate and dramatize holocaust denial and its rebuttal. The films’ staged cross-cultural miscommunications are catalogues of xenophobia. Perhaps because the UK offers plenty of targets but a more restricted audience, Americans are the target of the British comic’s stings. Yet Kazakhstan in its pastiche version of ‘Kazakhstan’ is placed front and centre as the antimodern heartland of backwardness. Islamic Kazakhstan feels the sting of this caricature but why is it important that Americans be critiqued, exposed and reformed? Why do the people skewered in the set-ups in the Borat films, who are often from marginal, unsophisticated, rural places, why do these people’s odd opinions matter? They are not important for themselves, nor is their humiliation personally deserved punishment for their naivete, callousness and lack of knowledge of others. These are figures of not just American but of all cultures’ worst impulses. They are us. This is the importance of having a star victim in the films, for example, Rudy Guiliani, who is caught, almost pants down or so it is made to appear, in one of Baron Cohen’s hoaxes. The segment with a seasoned public figure bridges the taboos of the ill-informed followers of conspiracy theories to show they permeate the highest echelons of society.

Or is this ‘us’? Because the films deal selectively with issues and problems, they do not deal with some of the most pressing issues of those same marginal people who are those who are the most likely to accept one of the paid roles as an extra set up as a victim or group of deplorables in Borat. The complaint of the extras lampooned in the films is often that they are disenfranchised. They are working to earn a living, experiencing economic and family stress, subject to inequitable practices and policies. The target audience seems white, middle class, ‘Western’, metropolitan and well connected to the world of information – within the limited horizon of Western media in which places such as Romania and Kazakhstan are absent.

While anti-semitism is certainly a problem in contemporary Islam, it is not a problem that particularly distinguishes Kazakhstan from other countries or cultures. Here the films are unfair. In actuality, when antisemitism comes up as a target in the films, Borat’s attitudes serve to expose the antisemitism of Western societies above all. That is, its is our own general xenophobia, our fears, that are parodied in these satires of reactionary others such as Baron Cohen’s hapless extras recruited to the films’ scenes. This is clumsily harnessed to Holocaust denial in the second film in the series, Borat Subsequent, in a way that attributes the Holocaust to Kazakh guards. The reality was that Eastern Europeans were recruited and also pressed into serving those functions by the Germans. The Borat films displace guilt from Europe to a Central Asian other, which constructs a wider Euro-American audience but obfuscates a historic tragedy – which is European. The origins of anti-semitism cannot be blamed on Islam or Central Asia or America.

The sins that the Borat films satirize are selective. The focus is not any taboo but taboos over which there is political disagreement. The films do not highlight, for example, child abuse and incest taboos although many of the scenes are replete with double entendres and references to abuse. The films leverage other taboos such as menstruation and menstrual blood as a shock tactic against the audience and participants in scenes. Yet I wouldn’t call Baron Cohen’s treatment feminist cinema. The films’ do attempt to foreground the humanity of the less fortunate but race, racism and economic class are also treated sotto voce. They are not the target of the films. Perhaps this reflects the weakness of Baron Cohen’s privileged transatlantic vision of the United States, a country with a much more felt history of racial oppression, slave labour and genocide of the Indigenous than the UK’s profits atop the historical pyramid of slavery capitalism?

What Baron Cohen’s victims make manifest is our willingness to go along with attitudes and practices that harm others and our refusal to acknowledge this. His films fail at exposing more entrenched structural racisms and xenophobias and even mobilize these tribal behaviours for Baron Cohen’s political satire. There is a specific audience in mind, for whom others are a form of cannon-fodder for Baron Cohen’s parody. The films raise ethical question: is it right to denigrate another society in order to expose an issue in one’s own society and in one’s own social class? Why displace guilt onto the Central Asian margins between Europe and China? These give the films a bitter taste. Perhaps they will provoke some conversations? They are matters are too important to just leave to satire.

-Rob Shields (University of Alberta)

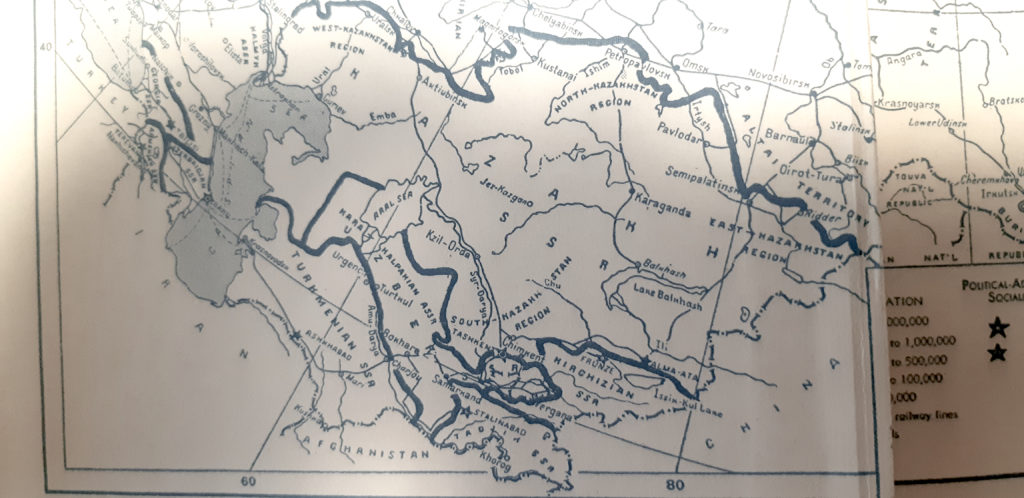

Many thanks to Kaven Baker-Voakes for access to his copy of the out of print map.